![]()

All my dreams were of ships; and one day a sea-captain who had come to dine with my grandfather put a hand on each side of my head and lifted me up to show me Africa, and another day a sea-captain pointed to the smoke from the corn-mill on the quays rising up beyond the trees of the lawn, as though it came from the mountain, and asked me if Ben Bulben was a burning mountain.

Once, every few months I used to go to Rosses Point or Ballisodare to see another little boy, who had a piebald pony that had once been in a circus and sometimes forgot where it was and went round and round.

He was George Middleton, son of my

great-uncle William Middleton. Old Middleton had bought land, then believed a safe

investment, at Ballisodare and at Rosses, and spent the winter at Ballisodare and the

summer at Rosses. The Middleton and Pollexfen flour mills were at Ballisodare, and a great

salmon weir, rapids, and a waterfall, but it was more often at Rosses that I saw my

cousin. We rowed in the river-mouth or were taken sailing in a heavy slow schooner yacht

or in a big ship's boat that had been rigged and decked. There were great cellars under

the house, for it had been a smuggler's house a hundred years before, and sometimes three

loud raps would come upon the drawing-room window at sundown, setting all the dogs

barking; some dead smuggler giving his accustomed signal. One night I heard them very

distinctly and my cousins often heard them, and later on my sister. A pilot had told me

that, after dreaming three times of treasure buried in my uncle's garden, he had climbed

the wall in the middle of the night and begun to dig but grew disheartened 'because there

was so much earth'. I told somebody what he had said and was told that it was well he did

not find it, for it was guarded by a spirit that looked like a flat-iron. At Ballisodare

there was a cleft among the rocks that I passed with terror because I believed that a

murderous monster lived there that made a buzzing sound like a bee.

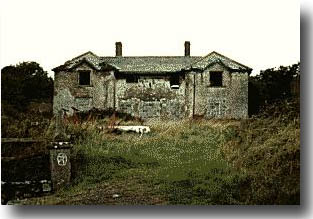

He was George Middleton, son of my

great-uncle William Middleton. Old Middleton had bought land, then believed a safe

investment, at Ballisodare and at Rosses, and spent the winter at Ballisodare and the

summer at Rosses. The Middleton and Pollexfen flour mills were at Ballisodare, and a great

salmon weir, rapids, and a waterfall, but it was more often at Rosses that I saw my

cousin. We rowed in the river-mouth or were taken sailing in a heavy slow schooner yacht

or in a big ship's boat that had been rigged and decked. There were great cellars under

the house, for it had been a smuggler's house a hundred years before, and sometimes three

loud raps would come upon the drawing-room window at sundown, setting all the dogs

barking; some dead smuggler giving his accustomed signal. One night I heard them very

distinctly and my cousins often heard them, and later on my sister. A pilot had told me

that, after dreaming three times of treasure buried in my uncle's garden, he had climbed

the wall in the middle of the night and begun to dig but grew disheartened 'because there

was so much earth'. I told somebody what he had said and was told that it was well he did

not find it, for it was guarded by a spirit that looked like a flat-iron. At Ballisodare

there was a cleft among the rocks that I passed with terror because I believed that a

murderous monster lived there that made a buzzing sound like a bee.

It was through the Middletons perhaps that I got my interest in country stories, and certainly the first faery stories that I heard were in the cottages about their houses. The Middletons took the nearest for friends and were always in and out of the cottages of pilots and of tenants. They were practical, always doing something with their hands, making boats, feeding chickens, and without ambition. One of then had designed a steamer many years before my birth and, long after I had grown to manhood, one could hear it- it had some sort of obsolete engine- many miles off wheezing in the Channel like an asthmatic person. It had been built on the lake and dragged through the town by many horses, stopping before the windows where my mother was learning her 1essons, and plunging the whole school into candlelight for five days, and was still patched and repatched mainly because it was believed to be a bringer of good luck. It had been called after the betrothed of its builder Janet, long corrupted into the more familiar Jennet, and the betrothed died in my youth having passed her eightieth year and been her husband's plague because of the violence of her temper. Another Middleton who was but a year or two older than myself used to shock me by running after hens to know by their feel if they were on the point of dropping an egg. They let their houses decay and the glass fall from the windows of their greenhouses but one among them at any rate had the second sight. They were liked but had not the pride and reserve, the sense of decorum and order, the instinctive playing before themselves that belongs to those who strike the popular imagination.

Sometimes my grandmother would bring me to see some old Sligo gentlewoman whose garden ran down to the river, ending there in a low wall full of wall-flowers, and I would sit up upon my chair, very bored, while my elders ate their seed-cake and drank their sherry. My walks with the servants were more interesting, sometimes we would pass a little fat girl, and a servant persuaded me to write her a love-letter, and the next time she passed she put her tongue out. But it was the servants' stories that interested me. At such-and-such a corner a man had got a shilling from a recruiting sergeant by standing in a barrel and had then rolled out of it and shown his crippled legs. And in such-and-such a house an old woman had hid herself under the bed of her guests, an officer and his wife, and on hearing them abuse her beaten them with a broomstick.

All the well-known families had their grotesque or tragic or romantic legends, and I often said to myself how terrible it would be to go away and die where nobody would know my story.

Years afterwards when I was ten or twelve years old and in London, I would remember Sligo with tears, and when I began to write, it was there I hoped to find my audience. Next to Merville where I lived was another tree-surrounded house where I sometimes went to see a little boy who stayed there occasionally with his grandmother whose name I forget and who seemed to me kindly and friendly, though when I went to see her in my thirteenth or fourteenth year I discovered that she only cared for very little boys. When the visitors called I hid in the hay loft and lay hidden behind the great heap of hay while a servant was calling my name in the yard.

I do not know how old I was (for all these events seem at the same distance) when I was made drunk. I had been out yachting with an uncle and my cousins and it had come on very rough. I had lain on deck between the mast and the bowsprit and a wave had burst over me and I had seen green water over my head. I was very proud and very wet. When we got into Rosses again, I was dressed up in an older boy's clothes so that the trousers came down below my boots, and a pilot gave me a little raw whiskey. I drove home on an outside car and was so pleased with the strange state in which I found myself that for all my uncle could do I cried to every passer-by that I was drunk, and went on crying it through the town and everywhere until I was put to bed by my grandmother and given something to drink that tasted of blackcurrants and so fell asleep.